Ana María Caballero is a multiple award-winning, transdisciplinary artist whose work interrogates the slippery boundaries between physicality and selfhood, language and perception, biological processes and their cultural narratives. Widely recognized across contemporary literature and digital art, she’s the first living poet sold at Sotheby’s and the first artist to receive a triple finalist nomination for the Lumen Prize.

Her practice has been featured by outlets such as ArtNews, Monopol, artnet, Poetry International, and BOMB, and her works reside in institutional collections including the Reina Sofía, MACBA, the Ashmolean, HEK Basel, Spalter Digital, and the Francisco Carolinum. A graduate of Harvard and the author of eight books, she’s also the co-founder of the digital poetry gallery theVERSEverse. She’s performed at the Venice Biennale, Art Basel, Gray Area, Fundación Telefónica, and Fundación March. Forbes named her one of 50 Latin Women to Follow in 2025.

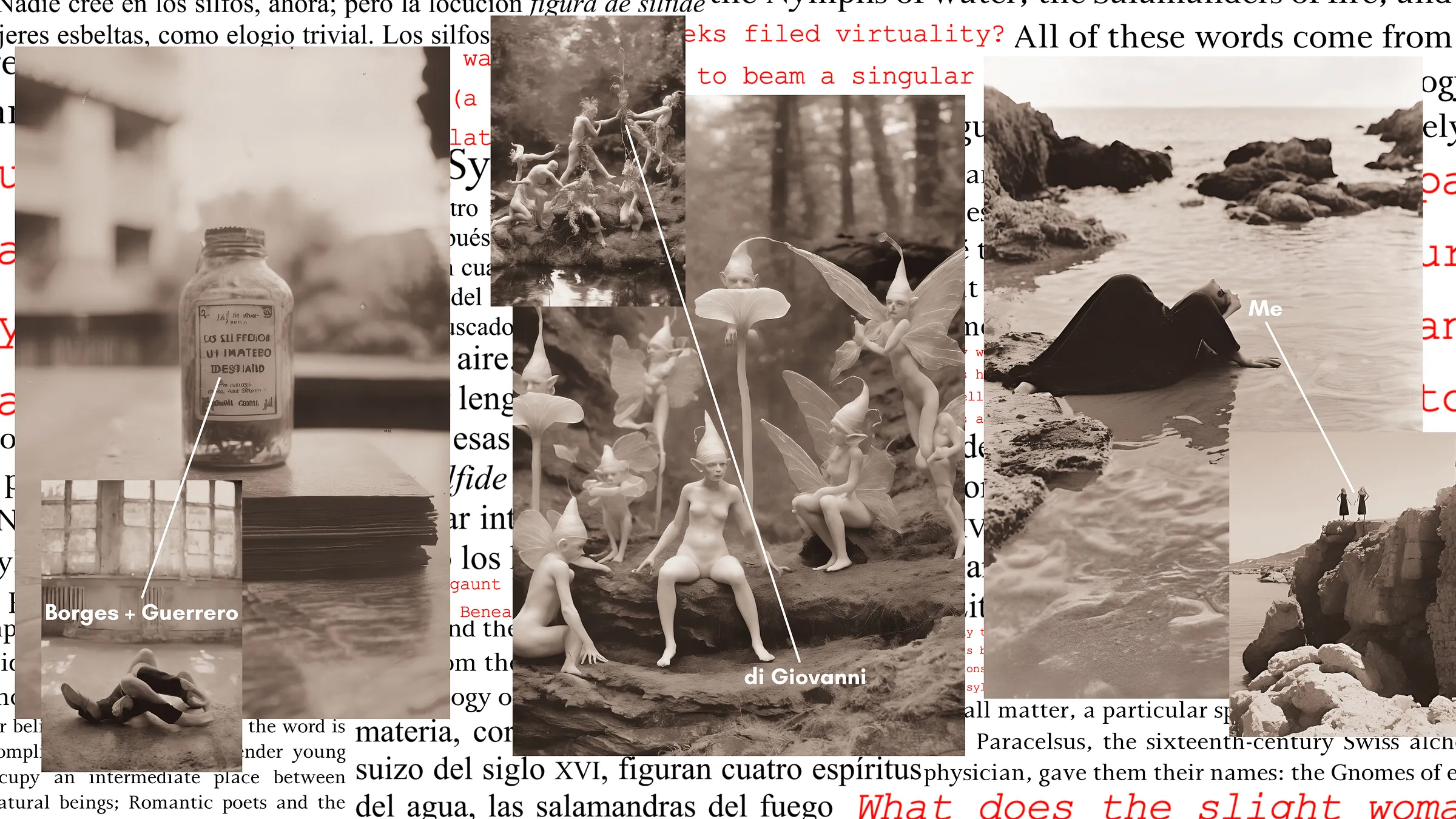

In her award-winning series

Being Borges, Ana María Caballero reimagines

The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges and Margarita Guerrero, probing the bounds of translation and the biases embedded within machine interpretation. Her work from the series,

The Sylphs, winner of the

2025 Lumen Prize in Still Image, asks a deceptively simple question:

What happens when language becomes literal through the visual?