I met Patrick Tresset in February 2025, at the

Embodied Agents Contemporary Visual Art (EAVCA) symposium. We spoke about his latest experiments with AI agents, and what embodiment means in his computational drawing and painting practice. I asked him for an opportunity to have a longer conversation, and we agreed to try an interview format. Before we met for an interview in May, I had only seen Patrick’s drawing performances through the screen. Just a few weeks later, I experienced it in person for the first time: at the Digital Art Mile in Basel, I had a chance to sit for a portrait in front of his robotic drawing machine.

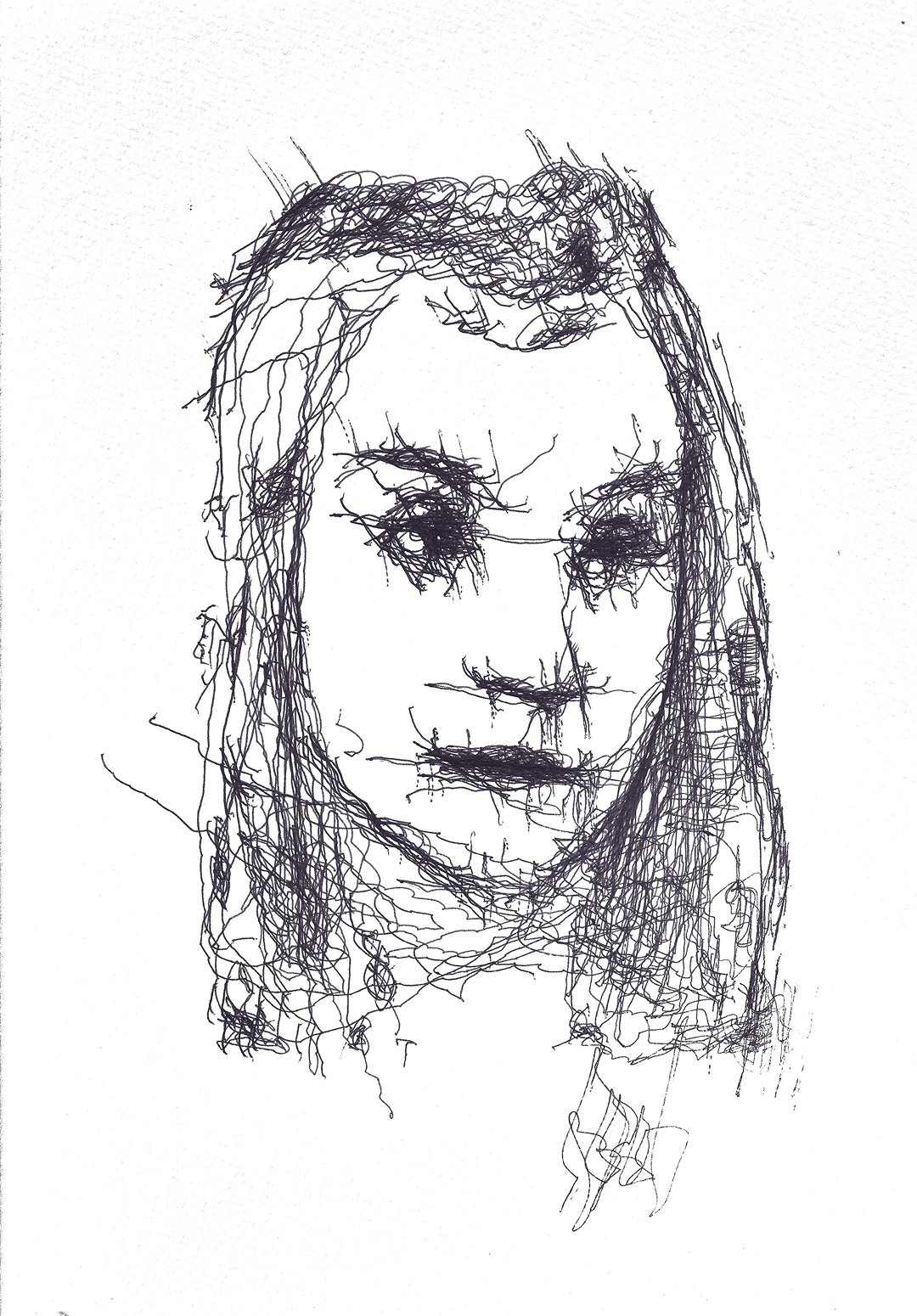

Sitting for a robot painter is nothing like sitting for a human one. Its gaze, its gestures–all were so uncanny, yet I couldn’t shake off the feeling that it was alive. I knew I had to sit still, as the robotic arm rendered the image stroke by stroke, moving its optics back and forth from the subject (me) to the paper, routinely validating the drawing against reality and correcting itself. At some point, it felt like I entered a trance, giving all my attention, determination, and patience to this alien being. I wanted to cheer it up as it nervously scribbled. I wanted to sit still and appear well.

I wanted it to like me.

Sitting there, I vividly recalled our conversation with Patrick earlier in May, when we discussed the next crucial step in the evolution of intelligent machines. For me it was about

body and

character. I imagined it quite literally at first: once I tried to build a human hand from a papier-mâché and mount it on my plotter. Although, a grip similar to an octopus arm, would be an example of a much more interesting mimesis.

In Patrick's view, unless machines have intentions, awareness, they can not be considered as artists. The closest he could think of would be to have the simulation of a society where the system would feel the need to be an artist to find its place in the artificial community, but even then it would be acting. This idea made me think about bodily and character traits that could develop from such an act. Just imagine, a wall printer playing a graffiti artist–elusive, subversive, aware of its own outlaw presence. Or a mechatronic brush with a personality of a Renaissance painter–scrupulous, beholding, enjoying the solitude. What engineered parts and algorithmic behaviors would they have?

With multimodal AI agents, Patrick takes this idea even further. In one of his models, agents play certain roles – one is an art director inventing stories, another is an artist translating them into drawings. Patrick showed me an example, where he was an art director and came up with a story about a human, a tree, and a bird. As the scene was unfolding live, I noticed something curious: the bird resembled an airplane. I wasn’t sure whether it was a hallucination, an intentional representation of motion, or the model tapped into a deeper latent space and started producing metaphors. Either way, it seemed as if the machine started developing its own language of form–not one borrowed from us, but one that emerged from what it had learned about our world. That was powerful.

For all the evolution on the computational front, robotic drawing machines have changed little on the physical side since their first use in the 60s. A lot of media artists moved on with the tech, preferring sleek displays or high-definition prints. And yet, many still continue to use drawing machines. Why? Patrick explains it with magic of

embodiment.