Simone Brauner: In your 2009 TED Talk, you scrolled through the new App Store asking, Where is art? Sixteen years later, how do you see that question now? Has the relationship between art and technology deepened, distorted or simply changed in unexpected ways? What does it mean to you today to ask this question again: Where is art now?

Golan Levin: Well, there’s still no “Art” category in the App Store! Clearly, a decade later, the blockchain has provided a platform on which creative coders can publish and sell software art, an opportunity which Apple did not deem worthwhile. In retrospect, I’m not surprised that a distributed, global, open, platform offered a ready solution for the arts that a commercial entity would not. I’m thrilled that so many creative people were able to find livelihoods and a marketplace for their work on the blockchain—particularly during the COVID lockdown, when opportunities to present one’s art had substantially dried up. I have to hand it to Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash, who had the foresight to see and understand this potential as early as 2014, when they created Quantum, the first NFT artwork.

Golan Levin, Golan Levin Makes Art That Looks Back at You, TED video, February 2009.

Unfortunately, despite the open nature of the blockchain, I feel that the nature of software art has nonetheless been deeply warped by the blockchain’s hype bubbles and market forces. The financial promise of the blockchain as a locus for art has distorted creative practices in countless ways, whether it’s an abundance of copycat work, or mountains of art that glorify money itself, or just biases in the kind of work that gets seen and becomes successful.

To take just one example, out of all the software art that is on the blockchain, only a tiny amount of it is interactive—yet interactivity is one of the truly distinctive potentials of software.

Since 2021, terms like “NFT”, “software art”, and “new media art” have come to be seen as interchangeable by many people, and even some galleries. But software art on the blockchain is such a narrow slice of the kind of art that has become possible with computation—cramped into a subset of possibilities defined by what’s technologically possible within a web browser. The relative absence of interaction modalities like cameras, microphones, and multitouch interfaces; or media types like random-access video, synthetic sound, or immersive 3D; or realtime communication with online databases or other users—represents a retreat to a baseline of multimedia work that has scarcely evolved since the 1990s—even if its idioms of generativity are much more current.

I also think about longevity and archival issues a lot, for software art. The App Store was terrible for this. For example, I released an interactive artwork on iOS in 2009, and Apple bricked it two years later, when they updated their SDK (software development kit). I recompiled it with the new SDK and released the updated version; a year later, Apple broke it again. I think this is just cruel to artists and small developers. It’s certainly not something that painters have to deal with. Again in theory, the blockchain presents a powerful solution for this—art written directly into the code of the blockchain, or so-called “on-chain” art, probably has good durability—but for anything larger than a few kilobytes, one has to continually “pin” (pay to host) the artwork or else it evaporates.

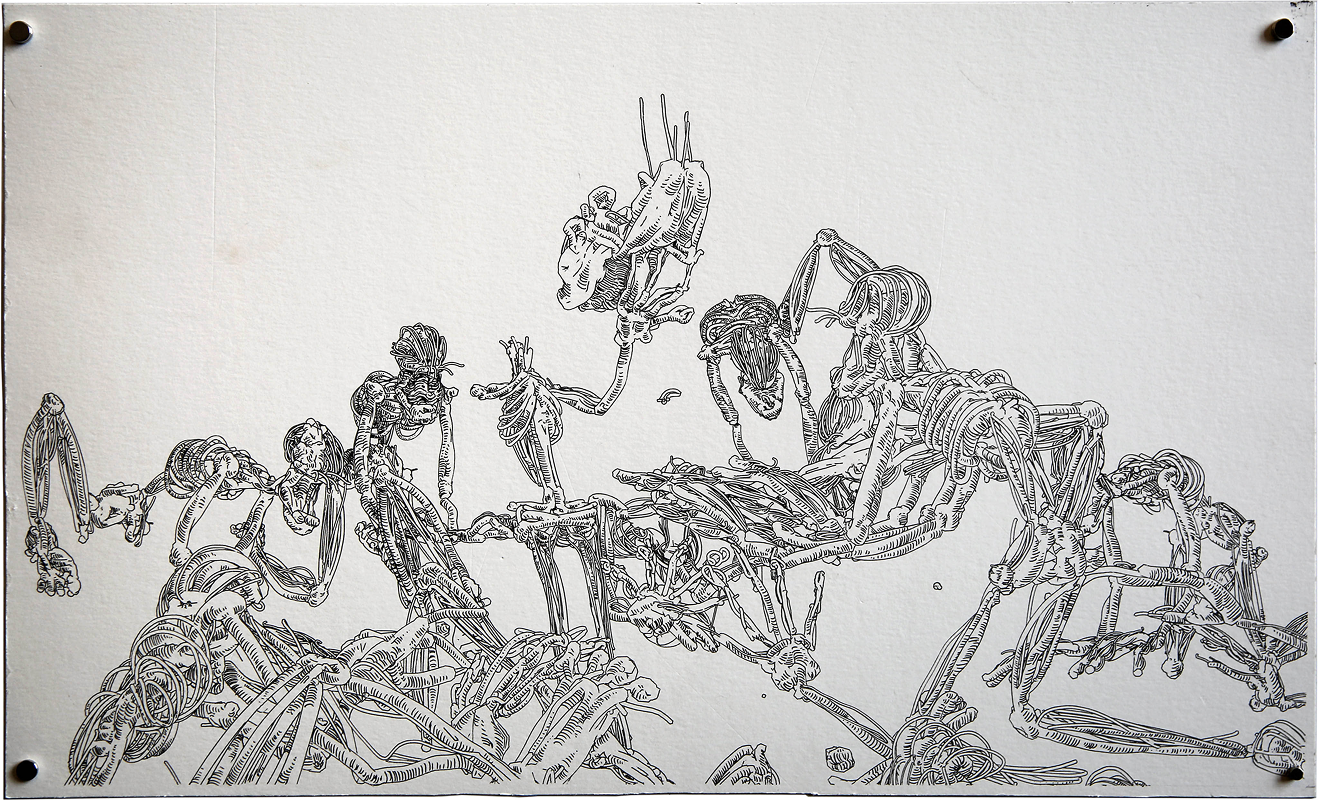

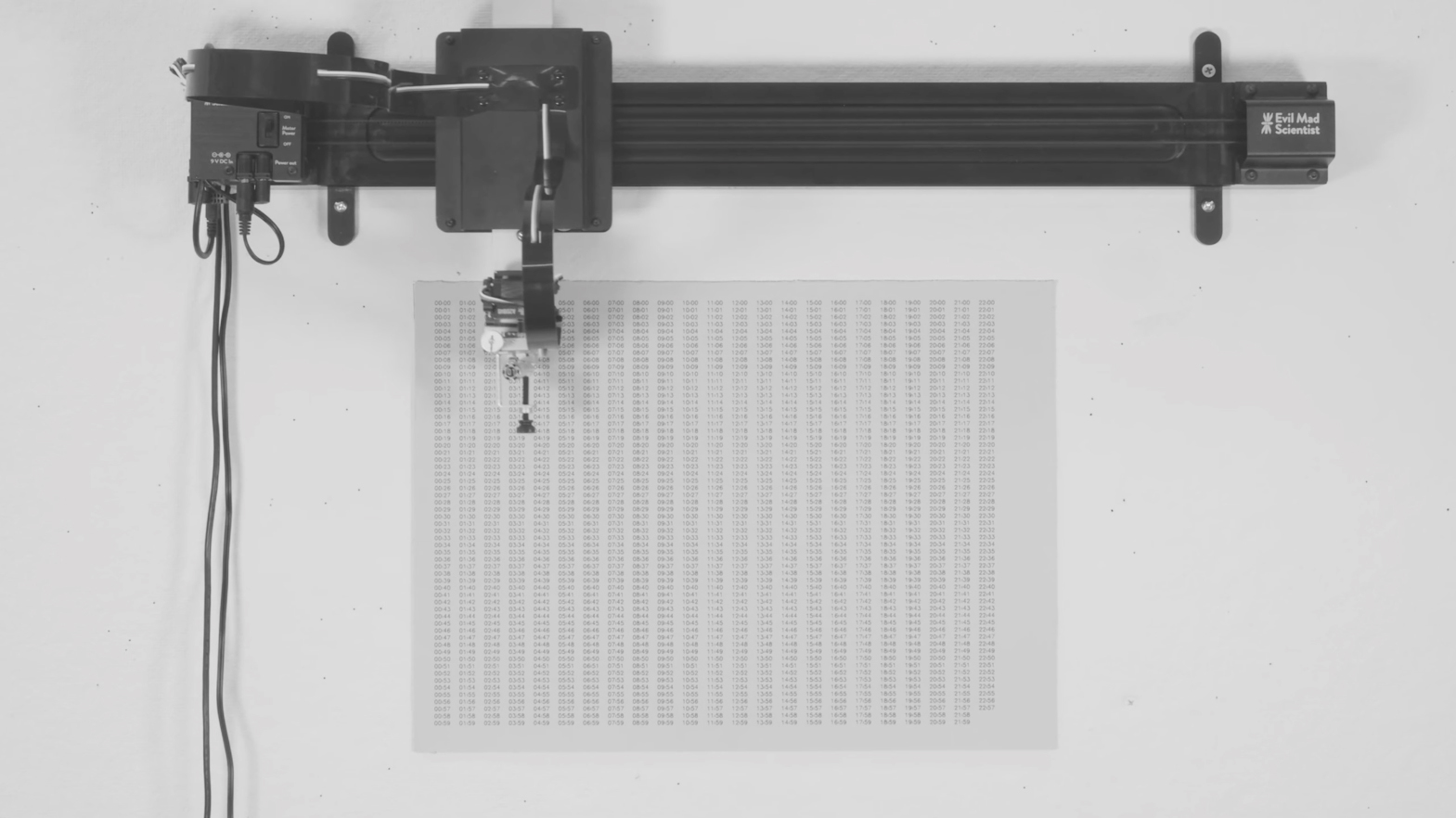

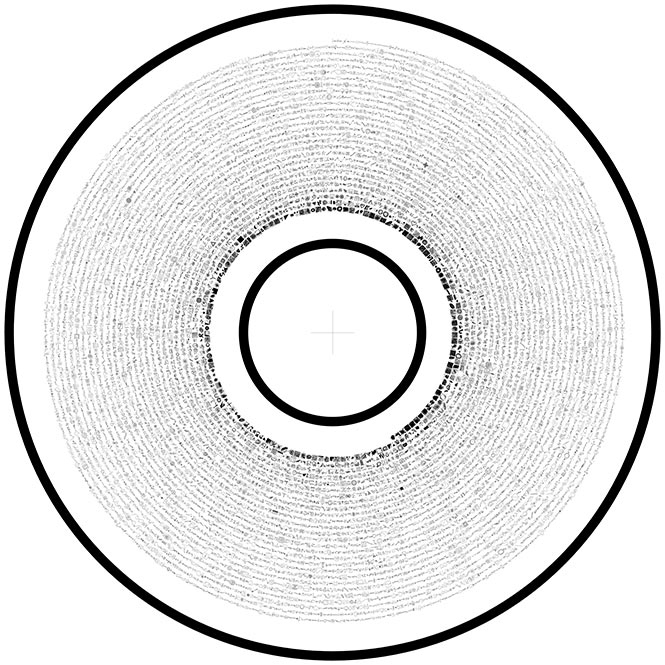

I think we are now in a kind of hangover from virtuality. Over the past couple of years, the rise of AI slop has increasingly made virtual media feel cheap, fungible and nugatory. This has been worsened by the isolation of our virtual lives in post-COVID Zoom-culture, and also a growing sense that the outrage-machines of social media are a kind of sickening force. My students tell me they feel ill from using computers—even (or perhaps especially) the ones who are adept at programming them. This is one of the main reasons I’ve shifted my teaching to focus on plotter art: making art with plotters is a kind of “touching grass”, leading to something truly real and unique that students can do with their creative coding skills. Twenty-five years ago I thought that making physical art was a quaint relic of the past; now, I value the creation of physical art as a critical practice of self-repair.