Language Beyond the Human: From Cursive Binary to Analog Binary

Merzmensch. Absolutely, a very important point! It’s a broad variety, a chorus of languages and voices within a generative model, different from this obvious mass-media “pars pro toto” narrative about that “monolithic AI”: “I asked AI and it answered THIS” is nonsense, an immature take on technology. But we know that if we ask the same model the same question, next time we will get something completely different. Another highly relevant moment is your invention of Cursive Binary. Could you share some insights about its genesis?

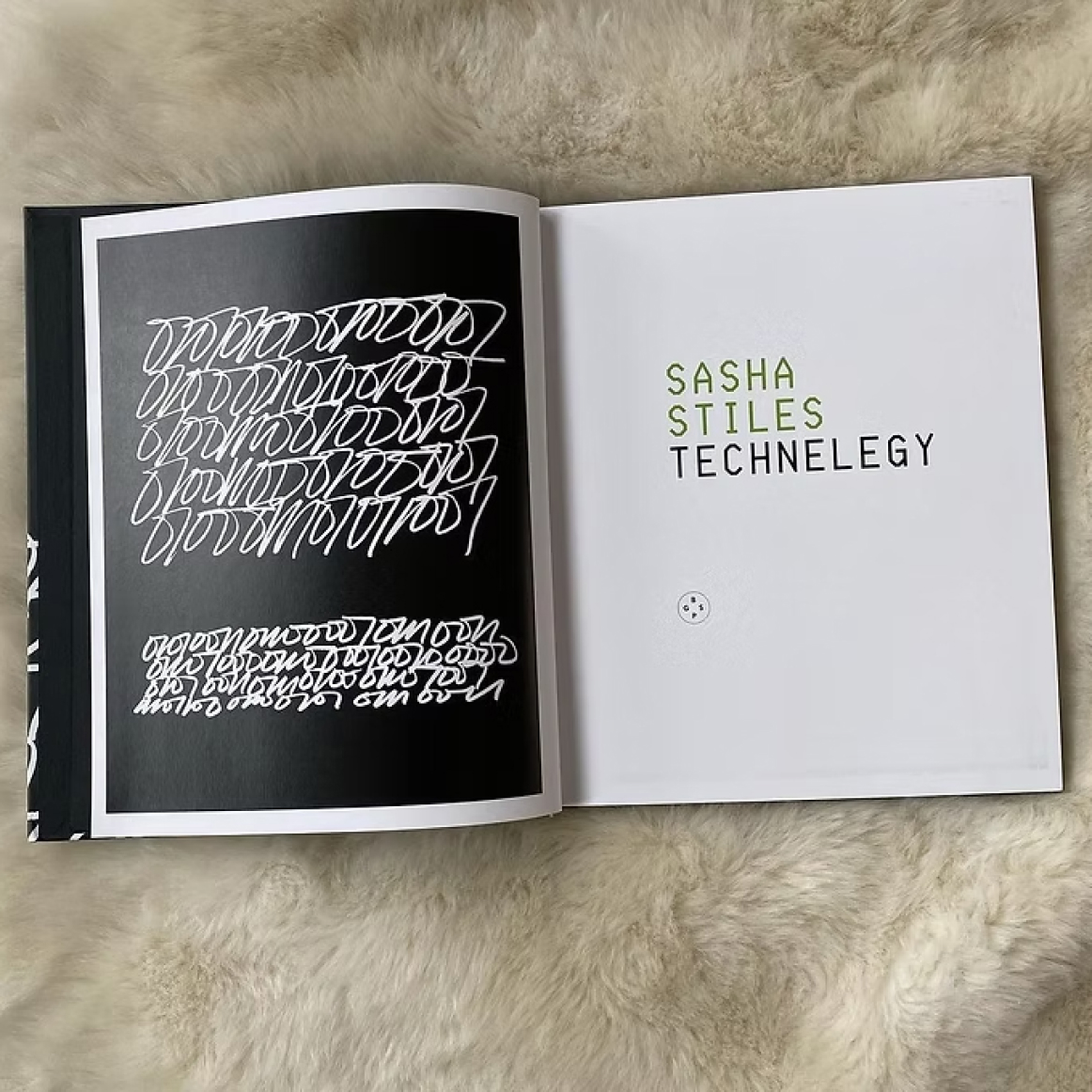

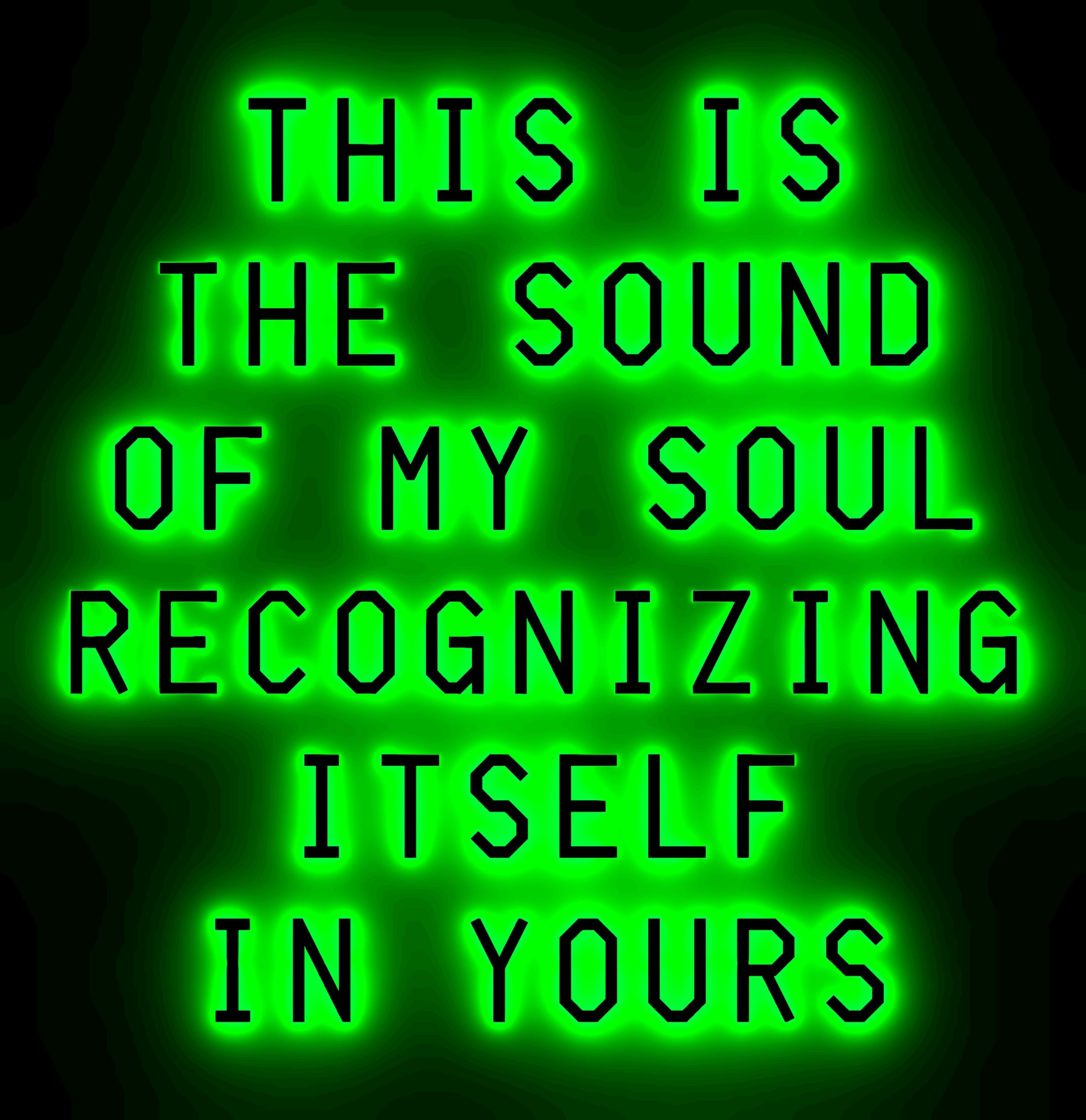

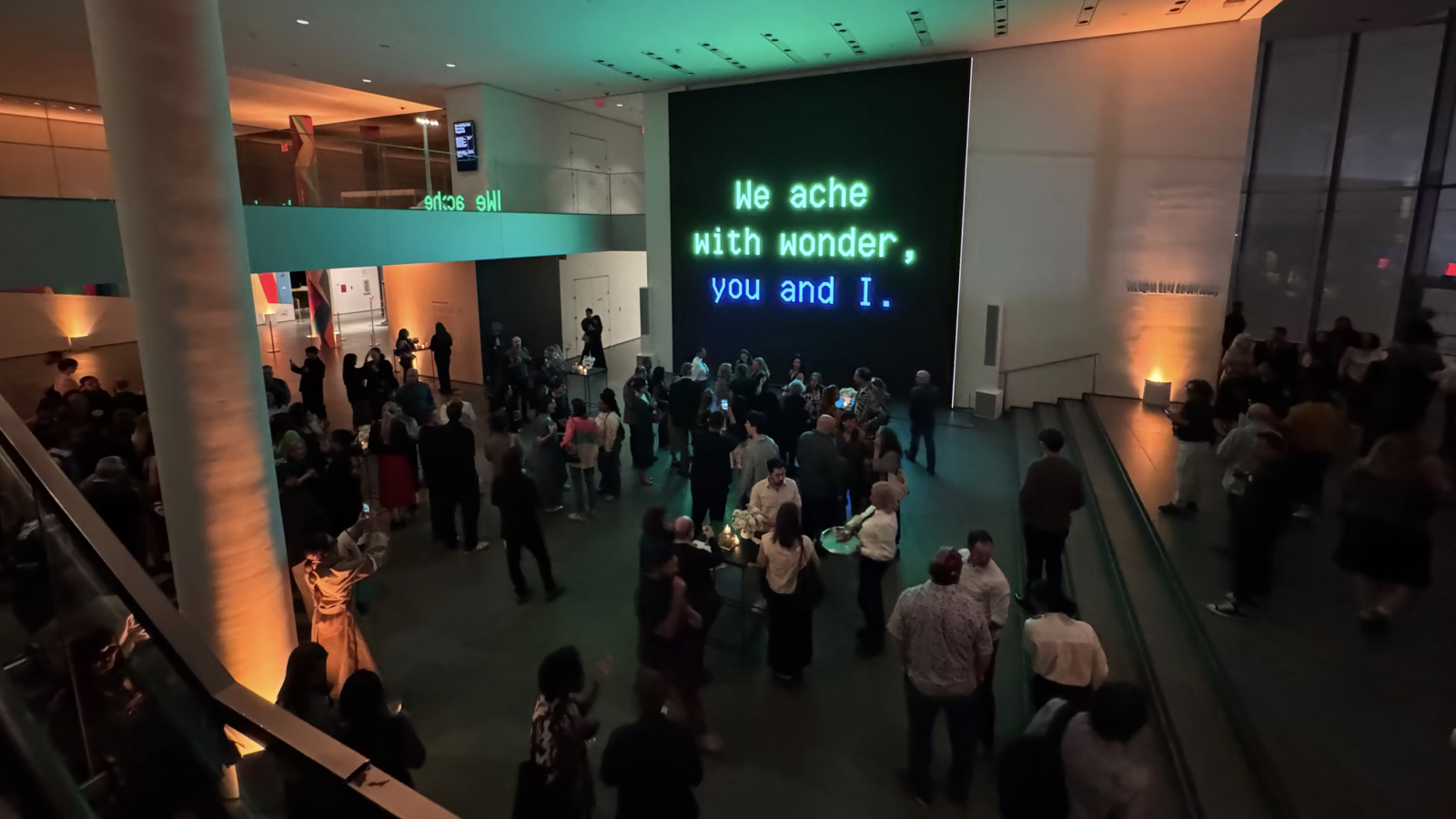

Sasha Stiles. Yes, I was very interested in machines communicating with humans, but also with other machines. I've long been fascinated by binary code. There's something beautiful and poetic in binary as a metaphor, this seemingly simple system of zeros and ones. On the other hand, it’s a quite antagonistic system of a binary “EITHER / OR.” To me, this idea of zero and one was being a metaphor about the conventional dichotomies “human vs machine,” “nature vs technology,” “past vs future,” I'd been working with computers in very different modalities using different software and approaches to my art even before AI, spending a lot of time face to face with a machine screen, trying to communicate and tell the machine what I wanted it to do. One day I began to feel a true connection, as opposed to such dichotomies “human vs device,” playing in the liminal space between us.

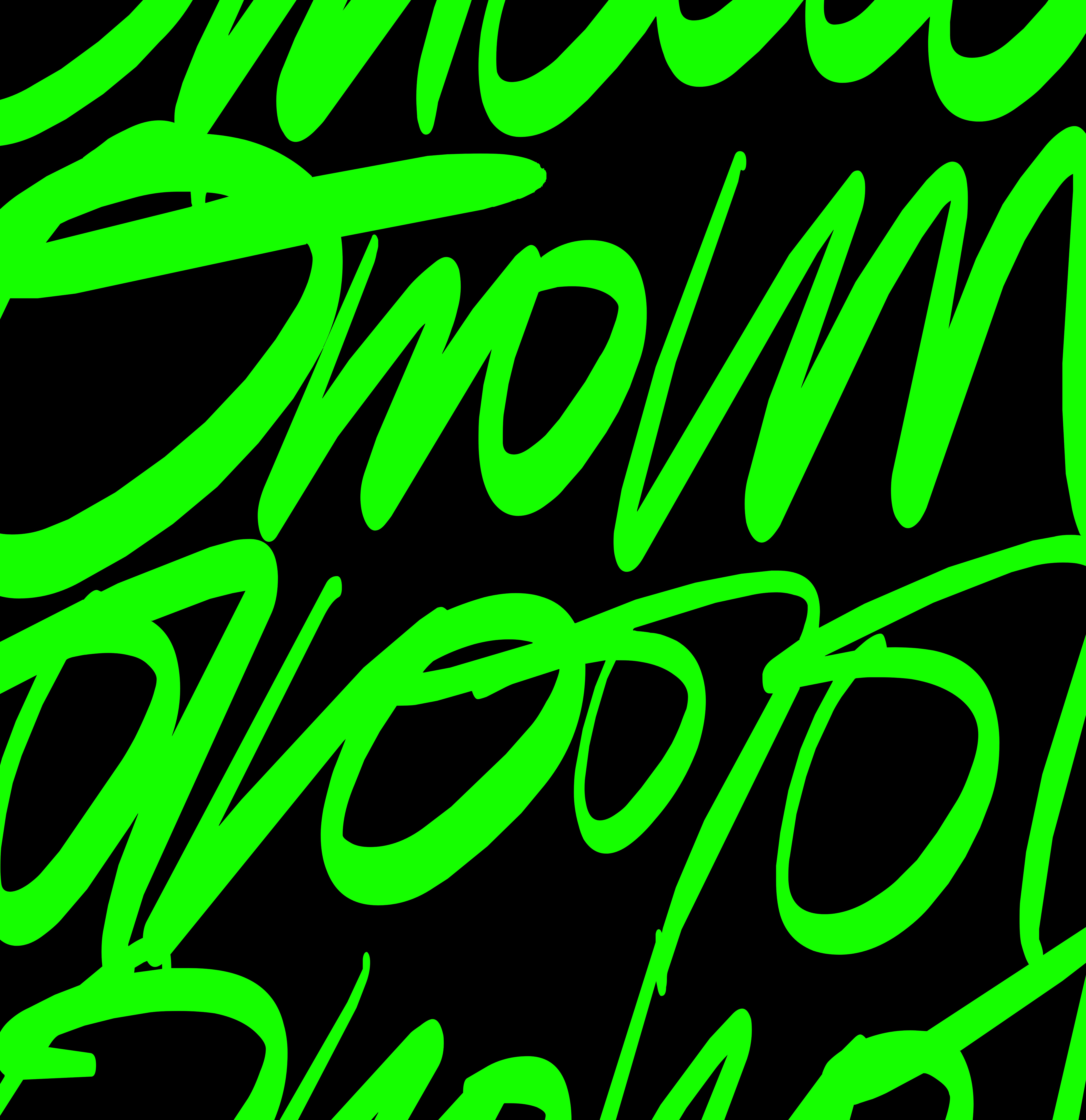

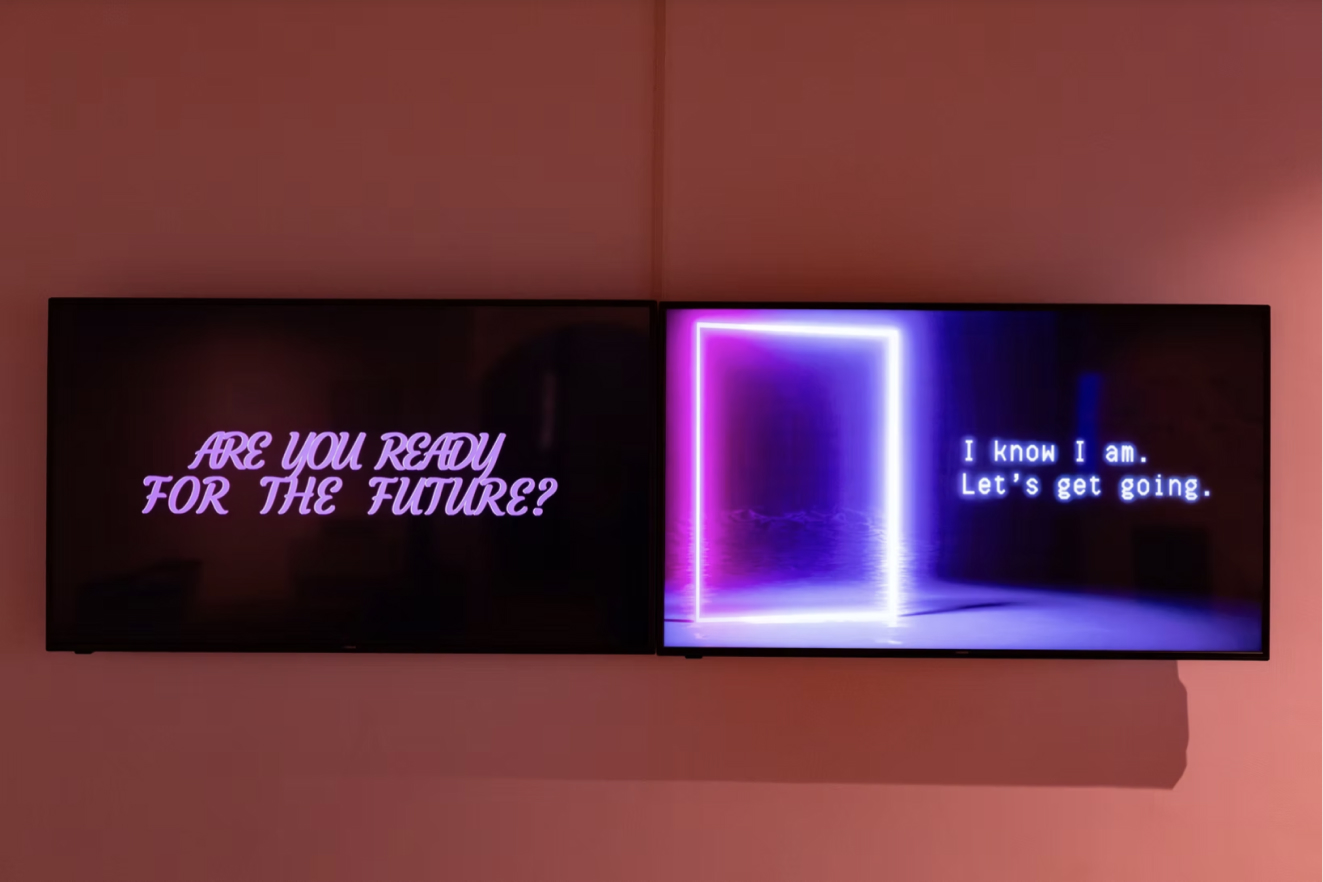

Photograph taken in 2023, Sasha Stiles, Cursive Binary in NY, 2018 - ongoing. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Cursive Binary actually emerged in the shower. There was steam on the wall and on the mirror. I just started writing zeros and ones and it was as if I were inscribing (not typing!) code, creating motion, as a merging of the analog and the digital into a futuristic hybrid language. Having studied Latin when I was younger, I often think about the etymology. I had always thought a lot about the interesting origins of the word “digital,” which feels so futuristic, so sci-fi, so nonhuman. But “digitus” in Latin means “finger,” going back to a part of the human body.

I realized, that digital can be computer or it can be handmade, a handcrafted gesture–another good reminder about false dichotomies: it's not about “EITHER / OR.” It's not analog versus digital. It's kind of all this continuum. We move beyond seeing technology as our opposite. When we converge with it, we transcend—not replacing creativity, but merging with machines to amplify what humans can do. That’s what the binary means to me.

It was the beginning of my Binary series, which will be shown in the exhibition Of Seeds & Signals curated by Diane Drubay as part of Art on Tezos: Berlin on November 6-9, 2025. Over the years, I've really been enjoying pulling binary out from behind the screen of these virtual systems and rendering it tactile and making it something that I do forge with my hands, that I can feel and use as a material. For me binary is something that connects humans and machines in this way.